Techniques

Preserving preparations of human body parts, animals and plants

Collecting human body parts has a long history. Relics, the supposed remains of saints, are just one example. It is only since the Renaissance that body parts have also been collected for non-religious purposes.

Initially, this mostly included skeletal remains. Drying was the only preservation technique available at the time, and bones were easier to dry than soft tissue. Most of the collected parts ended up in naturalia cabinets and cabinets of curiosities.

Wet specimens

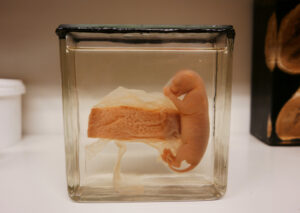

From the seventeenth century onwards, specimens were preserved in fluids, an art which would make the Amsterdam anatomist Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731) world-famous. Initially, alcohol (about 60%) was used as the preserving liquid, but at the end of the nineteenth century formalin was used as well. These new conservation methods made it possible to prevent all kinds of tissue and organs from decaying. This allowed them to be placed in glass jars and bottles to be studied for years.

Dry specimens in the cabinet of Jacob Hovius

Dry specimens in the cabinet of Jacob Hovius

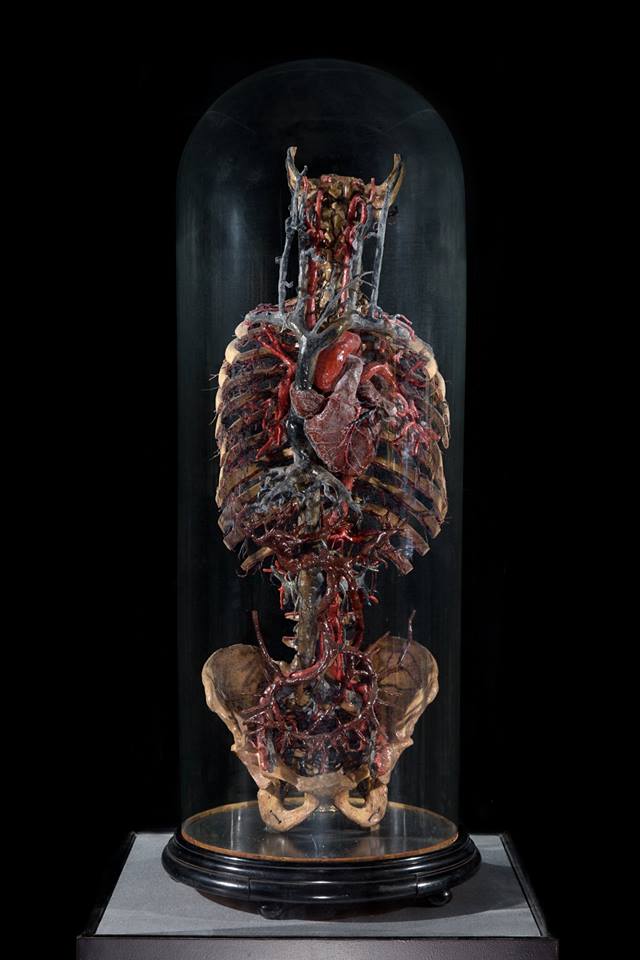

Injecting

Ruysch also injected his specimens with a wax-like substance that he would usually colour with a red pigment. This allowed him to reach even the smallest of capillaries. This technique gave his preparations a pinkish hue. Ruysch applied this technique to increase the visibility of tissues to better understand the anatomy. However, due to the colouring, his preserved children’s heads and hands gave the impression of still being alive. Ruysch enhanced this effect by giving his specimens little lace hats and cuffs. Ruysch also injected tissues and organs, which he subsequently embalmed and dried.

His method of injecting tissues with coloured wax-like substances was used until the nineteenth century. The collection of father and son Vrolik also features both wet and dry preparations of this type. Examples of dried and wax-injected organs from the Vrolik collection include placentas and penises, but mostly human and animal hearts. In the case of some hearts, one half has been injected with red wax and the other half with a dark blue wax, to make their anatomical structure more visible. After drying, most of the dried organ and tissue specimens were coated with shellac.

With coloured wax injected model of a human torso

With coloured wax injected model of a human torso

Jars

Until the nineteenth century, the method for storing and sealing specimens in jars barely changed. Samples were suspended in the jar using horsehair. The jars were sealed with a slate plate that was attached to the top of the jar using sealing wax. A pig’s bladder was then stretched over the top, to which a lacquer was applied after drying, which was usually red in colour. The jars in the Vrolik collection remain in their original state and can be recognized by their red seal. The same goes for the preparations that are part of the Hovius-Bonn collection.

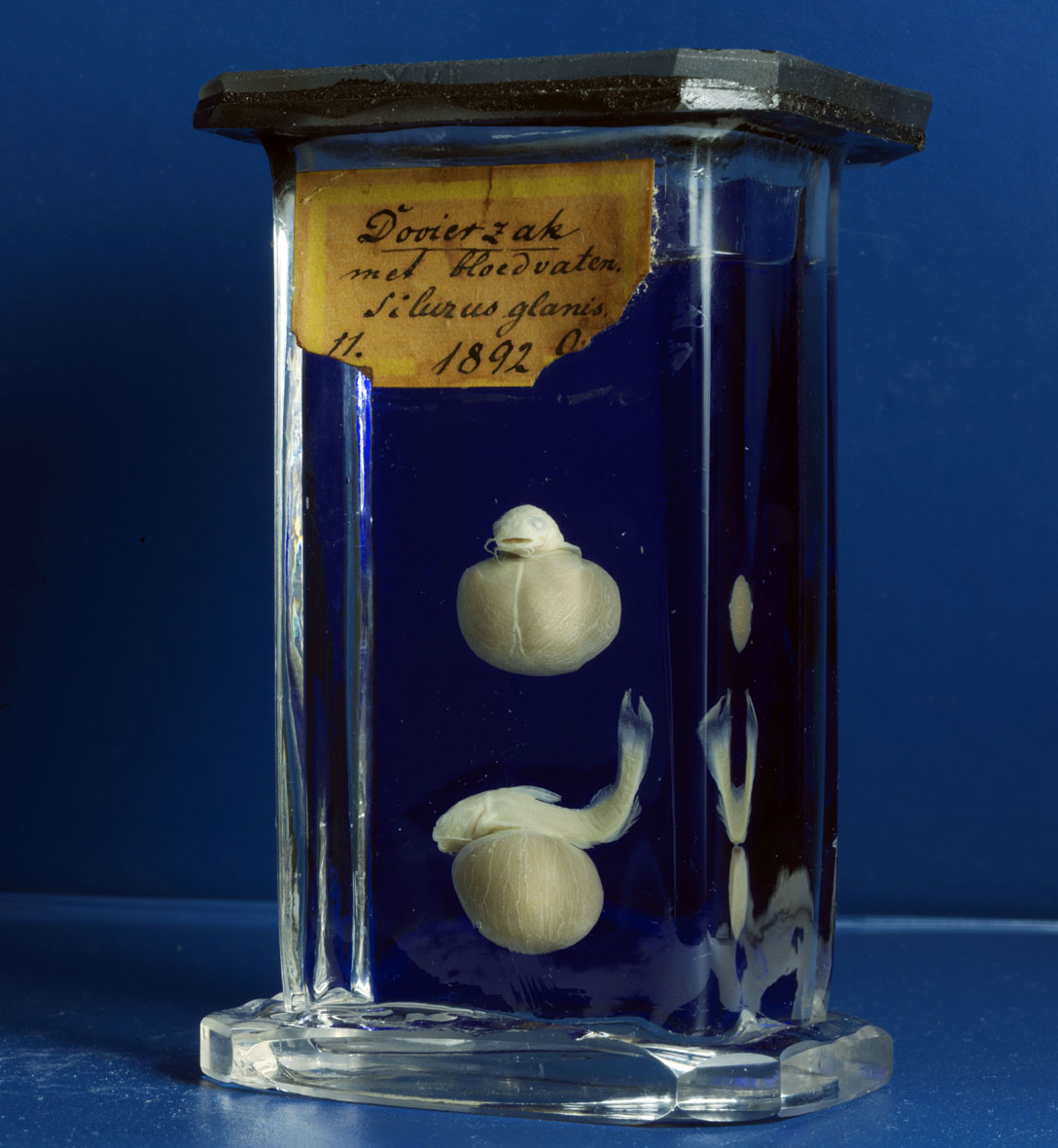

Every single jar and bottle used to store the specimens was round. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century, during the professorate of anatomist Georg Ruge, that square jars became available. They had one important advantage: the appearance of the specimens in the jar was no longer warped by the curve of the glass, so square jars especially benefited their educational purpose. For this reason, from around 1900 onwards, most new specimens were kept in square jars, suspended on a frame or fixed to a small glass plate. Specimens that had to be taken out of the jar frequently for research or lessons in the dissecting room would often be put in round bell jars. During this time there was a growing distinction between the research collection that was kept in a depository and the museum collection that was on display for students and scientists.

An anatomical preparation from the Vrolik collection with its original red sealing

An anatomical preparation from the Vrolik collection with its original red sealing

In the course of the first decades of the twentieth century, dark blue plates of glass were added to the jars under the supervision of anatomist Lodewijk Bolk to increase the visibility of the specimens even further. The pale specimens stand out clearly against the dark blue background. In the current museum, the majority of the specimens that form the systemic part of the collection is kept in square jars. The stark contrast between the specimen and the blue glass is immediately noticeable.

Restoration

Between 2003 and 2010, most of the wet specimens that are part the collection of the museum were restored. The main aim was to preserve the original state of the specimens. The original labels, glassware and seals were kept whenever possible. Specimens that had sunk to the bottom of their jars were suspended once more. However, all specimens that were originally preserved in formalin (about 4%) were transferred to a new liquid, Kaiserling III. This liquid largely consists of glycerol, water and sodium acetate and is virtually harmless, unlike the formalin solution.

One of Bolk's preparations, recognizable by the square jar and the blue slide made from glass

One of Bolk's preparations, recognizable by the square jar and the blue slide made from glass